O. Alan Noble has written for the Atlantic, Vox, Christianity Today, the Gospel Coalition, and First Things. The author of Disruptive Witness, he is one of the most perceptive evangelical cultural analysts working today.

Dr. Noble (PhD, Baylor University) is associate professor of English at Oklahoma Baptist University, cofounder and editor in chief of Christ and Pop Culture, and an advisor for the AND campaign. His latest book has gained significant acclaim. You Are Not Your Own: Belonging to God in an Inhuman World has been reviewed positively by some of the evangelical world’s leading voices, including Tim Keller, Michael Wear, Karen Swallow Prior, and Tish Harrison Warren. He explains this cultural moment in a way I have not seen articulated elsewhere, a way of understanding Western society I found both illuminating and practical.

In a day marked by tragedy, suffering, and despair, when so many have settled for survival, Noble writes that “Christians have an obligation to promote a human culture, one that reflects the goodness of creation, the uniqueness of human persons as image bearers, and Christ’s love.”

However, he notes that we are better at “helping people cope with modern life” than we are at “undoing the disorder of modern life.” For example, we help people deal with the symptoms of pornographic addictions but seldom grapple with a culture that glorifies sex as a means of existential justification.

Our root problem is “a particular understanding of what it means to be human: we are each our own, we belong to ourselves.” Noble explains:

“To be your own and belong to yourself means that the most fundamental truth about existence is that you are responsible for your existence and everything it entails. I am responsible for living a life of purpose, of defining my identity, of interpreting meaningful events, of choosing my values, and electing where I belong. If I belong to myself, then I am the only one who can set limits on who I am or what I can do. No one else has the right to define me, to choose my journey in life, or to assure me that I am okay. I belong to myself.”

However, “the freedom of sovereign individualism comes at a great price. Once I am liberated from all social, moral, natural, and religious values, I become responsible for the meaning of my own life. With no God to judge or justify me, I have to be my own judge and redeemer. This burden manifests as a desperate need to justify our lives through identity crafting and expression. But because everyone else is also working frantically to craft and express their own identity, society becomes a space of vicious competition between individuals vying for attention, meaning, and significance, not unlike the contrived drama of reality TV.”

This is a profound diagnosis of what is wrong with our culture, one that deserves our full attention and practical reflection.

“The fundamental lie of modernity”

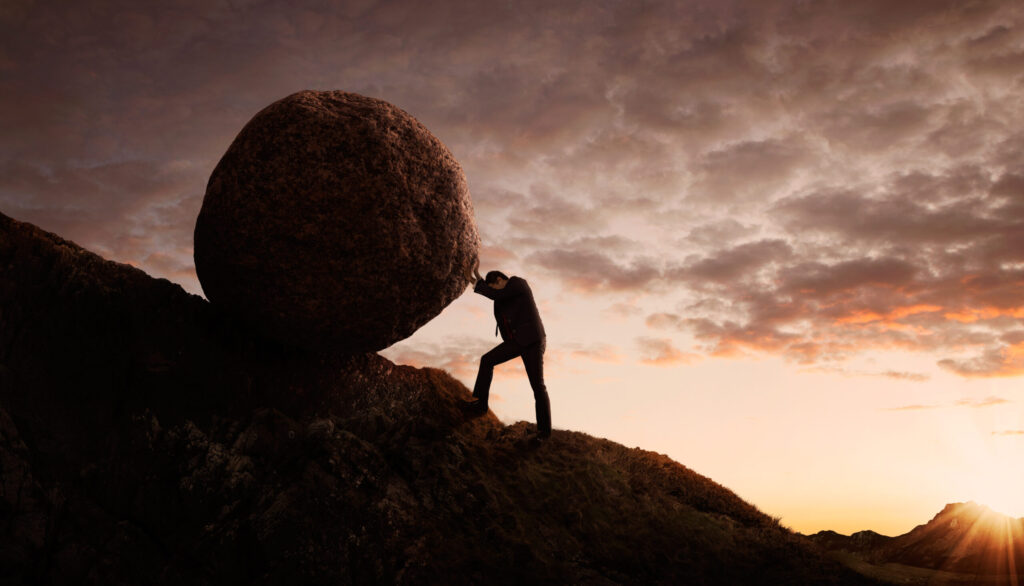

Noble labels as “Affirming” those people who respond by trying harder to do better, seeking “ever greater heights of self-mastery and excellence.” He calls others the “Resigned,” those who accept that they will never successfully compete and thus “turn to the allure of despair, killing time with immersive entertainment until death comes or circumstances change.”

According to Noble, “This is the fundamental lie of modernity: that we are our own.” He writes, “Until we see this lie for what it is, until we work to uproot it from our culture and replant a conception of human persons as belonging to God and not ourselves, most of our efforts at improving the world will be glorified Band-AIDS.”

He sketches numerous illustrations of his thesis, from the epidemic of mental illness to the “burn out” so many are experiencing, the damage to our environment by self-centered consumption, and the plague of pornography and other sexually immoral behaviors.

When we must justify ourselves in such a world, we insist on self-autonomy while constantly seeking the affirmation of others. We define meaning as something we feel, a “subjective, internal experience, not an external reality.” We impose meaning on our lives rather than aligning our lives with inherent meaning.

This arrangement only works so long as we all share a concern for human solidarity and mutual benevolence and we choose to live peaceful, orderly lives. But as rising global terrorism and domestic mass shootings show, many do not make this choice.

Even our commitments to our spouses, children, and community are framed by our limited commitment to their absolute freedom and by our desire for personal fulfillment.

“Pursuing our own conception of the good life”

Society helps us justify ourselves through stories of others who have done what we aspire to do. We are also encouraged to help those who deserve our compassion through challenges that are not their fault or choosing, what the philosopher Michael Sandel calls “luck egalitarian” philosophy.

Thus we are obligated to care for the impoverished and others who are victimized by our society. Of course, determining which members of society appropriately qualify for such help is highly arbitrary. Alternately, we can follow David Foster Wallace’s encouragement to help people “as if” they deserved our assistance. In either case, we are defining our worth by our self-driven choice to help others.

We can then use social media to seek the affirmation we yearn to feel. And we can use medical advances to align our bodies with our feelings and with the affirmation of others. We can seek rituals that solemnize our choices (such as polyamorous “wedding” ceremonies) and medicate ourselves when our drive for meaning proves unsuccessful.

We can learn through digital resources how to maximize the efficiency of every dimension of our lives, from sleeping to eating to working and relationships. And we engage in identity politics to join groups that affirm (and often harden) our choices in opposition to others.

As Noble notes, “If we are hopelessly our own and belong to ourselves, then there can be no substantial common good for us to work toward, politically or socially. The best we can do is try to stay out of each other’s way.” He cites the influential claim of John Rawls that “freedom consists in pursuing our own conception of the good life while respecting the rights of others to do the same.”

Technology enables us to stay unattached to others, from remote work to remote shopping to remote relationships to remote entertainment to even remote sex (through pornography).

The bad news: you are not your own

Here’s the problem: “Instead of a common good, we have billions of private goods.” There can be by definition no “common good” to seek if no “common good” exists. As Noble notes, “The goal of our striving cannot be reached because it is self-defined. The image of our fulfilled life is forever shifting.”

In addition, society keeps creating new tools for solving our problems that often make things worse. Fast food and other prepackaged foods give us more time to be more competitive; energy drinks give us more alertness for work; online dating makes relationship-seeking more efficient; smartphones enable us to feel connected to society. But the cost to our physical, relational, and psychological health is extreme.

And we are constantly chasing the validation of others which gives the lie to the quest for “self-sufficiency.”

Educational meritocracy drives children to burnout; capitalism drives their parents to an all-consuming productivity. Social media drives its users to measure themselves by the “likes” and “follows” of others, many of whom they barely know (if at all).

Some (the “Affirming”) take on this challenge through a never-ending quest for success at the cost of overwork and exhaustion (which they bear proudly as the cost of their success). Others (the “Resigned”) decide that they cannot compete successfully and “find an alternative space to pursue existential justification.” They compete not through graduate schools but through video games. They express their hope for meaningful relationships not through dating and marriage but through pornography.

Some move between the two poles depending on their circumstances. But Noble believes “Resignation has by far the strongest pull at our moment in history” as many of even the Affirming eventually learn that they cannot do enough to be enough.

As a result, many divert themselves from their challenges through the artificial world of social media and video games. Others choose marijuana, psychiatric medications, or other drugs and substances. We mask our deep disquiet with external appearances of success and happiness. But the prevalence of “deaths of despair” (suicides, alcohol-related deaths, and drug overdoses) and the epidemic of depression driven by feelings of inadequacy illustrate the pain we cannot resolve through self-reliance.

The good news: you are not your own

Noble offers us a solution rooted in Paul’s declaration: “Do you not know that your body is a temple of the Holy Spirit within you, whom you have from God? You are not your own, for you were bought with a price. So glorify God in your body” (1 Corinthians 6:19–20).

To repeat, “You are not your own.”

Noble notes that “from the Garden of Eden, humanity’s fundamental rebellion against God has been a rebellion of autonomy.” Consequently, “If we belong to ourselves, we are radically free—with all the accompanying glory and terror. But if we belong to God, then our experience of belonging in the world has limits that we have not freely chosen. And some of those limits will defy a value system based on efficiency and measurable harm.”

We should concede that “the turn toward autonomy in the West was prompted, in part, by horrific abuses of authority, hierarchy, religion, and tradition. When the king, the priest, and the banker all openly collude to rob and oppress you for their personal gain, which they declare to be their divine right, you begin to doubt the entire idea of modernity.” I would add that the same is true today as clergy abuse scandals continue to undermine the moral authority of the church while Vladimir Putin’s immoral invasion of Ukraine gives the lie to autocracy.

The answer, however, is not to abandon our need to belong to something or someone outside ourselves. It is to turn to the One who alone can lead us to our highest purpose and personal best.

We should submit our lives to God because he made us and knows what is best for us. He designed us to worship him and to belong to him as people. And because the One who made us died for us that we might be freed from bondage to sin and joined with him.

The consequences of belonging to God

When we respond to the lordship and mercy of Christ, we are relieved of the responsibility for justifying our existence. And we are given “a specific set of laws for determining right actions, which in their simplest form amount to loving God and loving our neighbor.” Noble adds that “from these two laws, humans can know what it means to act rightly in any circumstance. And the more we grow in wisdom and understanding, the better we can discern and address sin in our lives.”

As a result, “Compared to the moral uncertainty of the contemporary anthology, belonging to Christ gives us the tremendous comfort of a beautiful and clear moral horizon. We know how we ought to act.”

Conversely, choosing to belong to God reveals our sinfulness to us. This revelation then drives us to even further submission to our Master, which further leads us from sin into the holiness and significance he intends for us.

When we choose to belong to God, there is no image for us to maintain because we were made in the image of God. There is no identity for us to discover or create because our identity is found in Christ’s love for us.

We then live in light of his existence, goodness, and providence, trusting that he will make of us what is for his highest glory and our greatest good. We do what is beautiful because it is beautiful. We serve others because we wish to serve them. We have no need to justify what we do, for we belong to the One who has already justified us and now works through us.

As we belong to Christ, we belong to the people and places where we live in him. We care for and serve our families, colleagues, and environment because we belong, not to belong.

Living by belonging to God

Noble closes not with a “five-step strategy” but with recommendations grounded in reality.

Grace: Abandon false hope that humans will make this world and their lives better in ways that truly matter and offer them grace.

Personal responsibility: We hope for justice and do what we can do to be faithful to our calling to make a difference. Nobel quotes T. S. Eliot, “For us there is only the trying. The rest is not our business.”

Supplication: Nobel writes, “True supplication is not passivity or resignation. It is an act of dependence upon God, which always involves obedience to his will. When we reach out in supplication before God, we don’t get to ignore injustice or the dehumanizing structures of society. But it does mean that our actions are done in reliance upon God.”

As a result, “If we belong to God, we can have faith that he is bringing about his justice and his redemption.” Our obligation is “to honor God with our lives” without “delusions of grandeur that we will save society” and yet without fleeing society.

Our calling is not to integrate with the culture but to reject its seduction while praying for its welfare. We call out the “false conception of the human person that assumes that I am my own and am solely responsible for making my life better.”

As Noble reminds us, “That is a lie. I am not my own but belong to Christ.”

Our job is to believe that God is redeeming the world and to join him where he calls us. Our calling is to desire the good of our neighbor (Galatians 6:10; Philippians 2:3–4) as a “lifelong project.” And to desire the goods that God defines as good, whatever others think and however they respond to us.

When we belong to God, we are free to serve our spouse, family, and community, whether they serve us or not. We reject the tyranny of the social hierarchy and meet needs in ways that are genuinely helpful to others and glorifying to God.

And we have the freedom to rest, not to “recharge” so we can work harder and longer or to consume socially expected content during our leisure, but to experience the presence of Jesus. We are free to be Mary at the feet of Jesus.

And we are free to engage our culture for meaningful progress as God leads and opportunity exists: “Wherever you are in your community, whatever sphere of influence you have, you are called to desire and pursue the good of your neighbor because we belong to Christ, not ourselves. Self-interest is simply not an option for us.”

Conclusion

When we know that we belong to Christ, we find comfort in life through knowing that “we are accepted and loved without reservation.” We are therefore free to love others however they respond to us.

And we find comfort in death by experiencing liberation from the quest to do enough to “die content” and the “haunting prospect of nonexistence.”

According to Noble, “We can be comforted that before God there is no burden to use our life efficiently, to accomplish enough or achieve enough, to do enough with our limited time to justify our life.”

This is because we are justified already through “him who loves us.”

And that is enough.